Trials: A Young Lawyer’s Perspective from Long Ago

The seminar was held at our annual trial lawyer’s convention in Suncadia, Washington and was moderated by preeminent and award-winning Washington State trial lawyer Paul Luvera. It was a highlight of my career as I rose to the take the stage with the senior Mr. Luvera looking on. I spoke about my trial experience to date and grappled with the honest human notion of “fear” as it relates to trial work. I have reproduced my written materials here for this blog and continue to believe that an honest and healthy fear of trial is what makes for great trial lawyers who are prepared to win:

Why I’m Terrified By Trial

By: Kristi McKennon

“Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear - not absence of fear.”

— Mark Twain

One need only walk the halls of any courthouse to see an abundance of those, particularly young lawyers, professing the absence of all fear. But the truth is that we all fear trials at some level; everyone of us, young and seasoned, shares my terror of trying a case. We share this terror because trials are wild and mostly out of our control. Trials are largely unpredictable. They are the crucible of our profession and they bring out the best and the worst in all of us. Trials take precious time from those we love, take risks with our and our clients’ money and, we hope, pay off in spades when the jury finds our cause to be just.

In my seven years as a trial lawyer, there has yet to be a 15-minute-period leading up to “Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury, will you please turn your attention to Ms. McKennon on behalf of the plaintiffs,” where I didn’t think I was going to die of anxiety. But what I’ve learned and what I now treasure is the power in the terror. The terror reminds us of the importance of our roll, the power of our story and the burden we carry. The terror is honest; the terror is pure and it’s real. We only win the battle at hand and the war that follows by embracing all of our emotions including fear, and being honest with our jury and ourselves.

The Brain: We attend “Reptile” CLEs and trial lawyer colleges to try to learn how to be lawyers who win over the minds of our jurors (and their hearts but that’s a topic for another day). We think a lot about what’s going on in our jurors’ brains but not a lot about what’s going on in our own. What I’ve learned is that this terror I feel, it is “reptilian.” I am becoming at that moment, the reptile to whom I am trying to appeal in the jury box. It is part of the body’s natural and most basic negative response to potentially harmful stimuli. And that jury, as we all know from having been bitten, is as potentially harmful as a coiled rattlesnake. I am at that moment a living example of a reptile. Fight or flight. I am the beady-eyed slithering thing that is panicked.

“Human anxiety is greatly amplified by our ability to imagine the future, and our place in it. 1”

— Joseph LeDoux

But, wait a minute; this is actually a good sign. When we become aware of the uncertainty and we know the burden we carry, it becomes incredibly rational to fear trials. (In fact I find that the more rational and wise a lawyer is on my own personal rating system, frankly, the more fearful she is of trial and more likely she is to admit it). The fear is human; the fear is a reminder of our limited control of the universe. The fear is based on our past-experiences, including our mixed bag of trial experiences. The wins are great, and the losses we try to forget, but our reptilian mind remembers.

The Theory: The key here is to embrace all of it and move away from the state of the reptilian mind of the jury we are trying to appeal to, to the more evolved cerebral cortex of the analytical beings we aspire to be in using our neomammalian mind.

"It is the distinction of our species, the seat of our humanity. Civilization is the product of the cerebral cortex."

– Carl Sagan

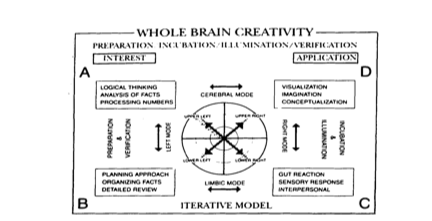

Another way to think of it is based on a modified version of the triune brain modeled above but divided in the left and right hemisphere of the brain, accepting what we all tend to know about the brain (the right brain is creative and the left brain is more logical and analytical). If you use both models together, you get this four-quadrant approach to the brain which tells us how to leave our pre-evolutionary fear and move to a state of enlightened “whole brain creativity.”2

When I found this model, above, it was a eureka moment for me because it embodied what I had been doing unwittingly in moving from the lower brain function of the reptilian mind’s fear to the higher functioning upper right and upper left quadrants of the cerebrum in trial: visualizing the moment. For me, and for many as I have learned in reading about this concept, visualizing every part of the trial and allowing it to slowly incubate in the mind before and even during trial, calms the fear. It does not dissolve the fear. The anxiety and the unknown live on if we are rational actors (and most of us are). It simply moves the mind from a state of reptilian fight or flight sweat-fest, to a more calm state of creativity and analysis. What I find is that when you visualize the opening and closing many times down to the detail of where you will stand and what the room looks like, it kicks your mind very quickly out of the reptile state and into the higher function. So, I sit there and I, it may seem odd, but I see it all happen in my mind before it happens and while it is happening. I therefore, move myself from the gut reaction of “C” (which is a necessary part of the cycle by the way) to the conceptualization of “D” and leave my primal fear in the dust. What I have done in prepping for trial in the weeks prior is all the work in “A” and then in “B” which prepared me to face my fear in “C” and, if I do it right, leads me to the perfect creative moment in opening statement at “D.” Ned Herrmann’s3 article on The Creative Brain is fabulous, by the way, and also encourages collaboration of those persons whose brains naturally start at different points on the cycle to achieve brilliant whole-brain work together and thus achieve greater results both individually and collectively. His theories encourage group work and group learning from different brain styles. He, I would extrapolate, would be a proponent of trying cases with a lawyer who is very different from you to achieve more creative results.

But first we have to move through the fear to the higher brain function of creativity. Mike Robbins4 of the Huffington Post Healthy Living has an awesome 7-point checklist of doing just that.

How to move through your fear in a positive way:

1. Admit it

Acknowledge your fear, tell the truth about it and be real. When we feel scared and are willing to admit it with a sense of empathy and compassion for ourselves, it can often take the edge off and give us a little breathing room to begin with.

2. Own it

Take responsibility for your fear and own it as yours, not anyone else's . . . .

3. Feel it

Allow yourself to feel your fear, not just think about it or talk about it (something I often catch myself doing). Feel it in your body, and allow

4. Express it

Let it out. Speak, write, emote, move your body, yell or do whatever you feel is necessary for you to express your fear. Similar to feeling any emotion with intensity, when we express emotions with intensity and passion, they move right through us. When we repress our emotions, they get stuck and can become debilitating and dangerous.

5. Let it go

This one is often easier said than done, for me and many people I work with. Letting go of our fear becomes much easier when we honestly admit, own, feel and express it. Letting go of our fear is a conscious and deliberate choice, not a reactionary form of denial. Once you've allowed yourself the time to work through your fear, you can declare "I'm choosing to let go of my fear and use its energy in a positive way."

6. Visualize the positive outcomes you desire

Think about, speak out loud, write down, or even close your eyes and visualize how you want things to be and, more importantly, how you want to feel. If your fear is focused on something specific like your work, a relationship, money, etc., visualize it being how you want it to be and allow yourself to feel how you ultimately want to feel.

7. Take action

Be willing to take bold and courageous actions, even if you're still feeling nervous. Your legs may shake, your voice might quiver, but that doesn't have to stop you from saying what's on your mind, taking a risk, making a request, trying something new or being bold in a small or big way. Doing this is what builds confidence and allow us to move through our fear.

References:

- Joseph LeDoux. Searching the Brain for the Roots of Fear. NY Times. (January 22, 2012).

Joseph LeDoux is a Henry and Lucy Moses Professor of Science, and professor of neural science and psychology at New York University. He is also the director of the Emotional Brain Institute. He is the author of many articles in scholarly journals, and the books “The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life” and “Synaptic Self: How Our Brains Become Who We Are.” ↩︎ - Ned Herrmann, The Creative Brain, The Journal of Creative Behavior: Vol. 24, No. 4 (1991). ↩︎

- William Edward "Ned" Herrmann (1922 - December 24, 1999) is known for his research in creative thinking and whole-brain methods. He spent the last 20 years dedicating his life to applying brain dominance theory to teaching, learning, increasing self-understanding and enhancing creative thinking capabilities on both an individual and corporate level. Herrmann's contribution to the application of brain dominance brought him worldwide recognition. In 1992, he received the Distinguished Contribution to Human Resource Development Award from ASTD. In 1993, he was elected President of The American Creativity Association. At Cornell University, he majored in both physics and music. He became Manager of Management Education for General Electric (GE) in 1970. His primary responsibility was to oversee training program design, covering topics like how to maintain or increase an individual's productivity, motivation, and creativity. ↩︎

- Mike Robbins. How to Move Through Your Fear in 7 Steps. Huffington Post Healthy Living. (11/26/2010).

Mike Robbins is a sought-after motivational keynote speaker, coach, and the author of the bestselling books Focus on the Good Stuff (Hardcover, Wiley) and Be Yourself, Everyone Else is Already Taken (Hardcover, Wiley). Mike and his work have been featured on ABC News and the Oprah radio network, as well as in Forbes, Ladies Home Journal, Fast Company, Self, the Washington Post, many others. He's also a regular contributor to Oprah.com and the Huffington Post. He has worked with clients such as Google, Wells Fargo, AT&T, Apple, Genentech, and more. Mike's books have been translated into ten languages. ↩︎